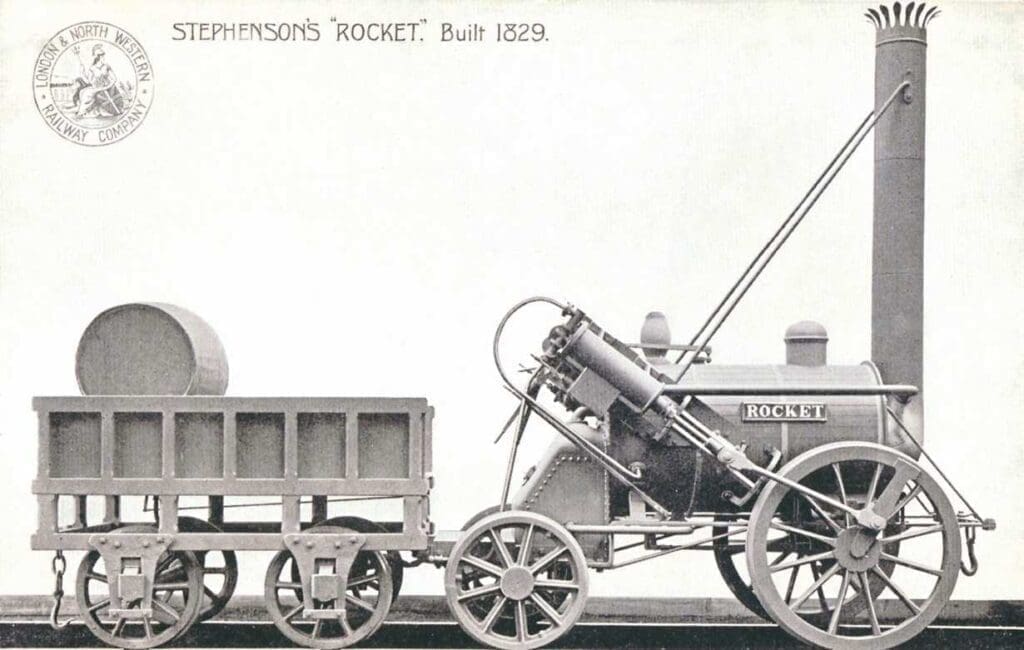

How much further can a locomotive go in terms of acquiring ‘legendary’ status than having a succession of full-size replicas built? Such is the worldwide fame of one of the most instantly recognisable steam locomotives of all – Stephenson’s Rocket.

This is just one of the many in-depth features found in the new book by Robin Jones, Legendary Locomotives, available now from Classic Magazines.

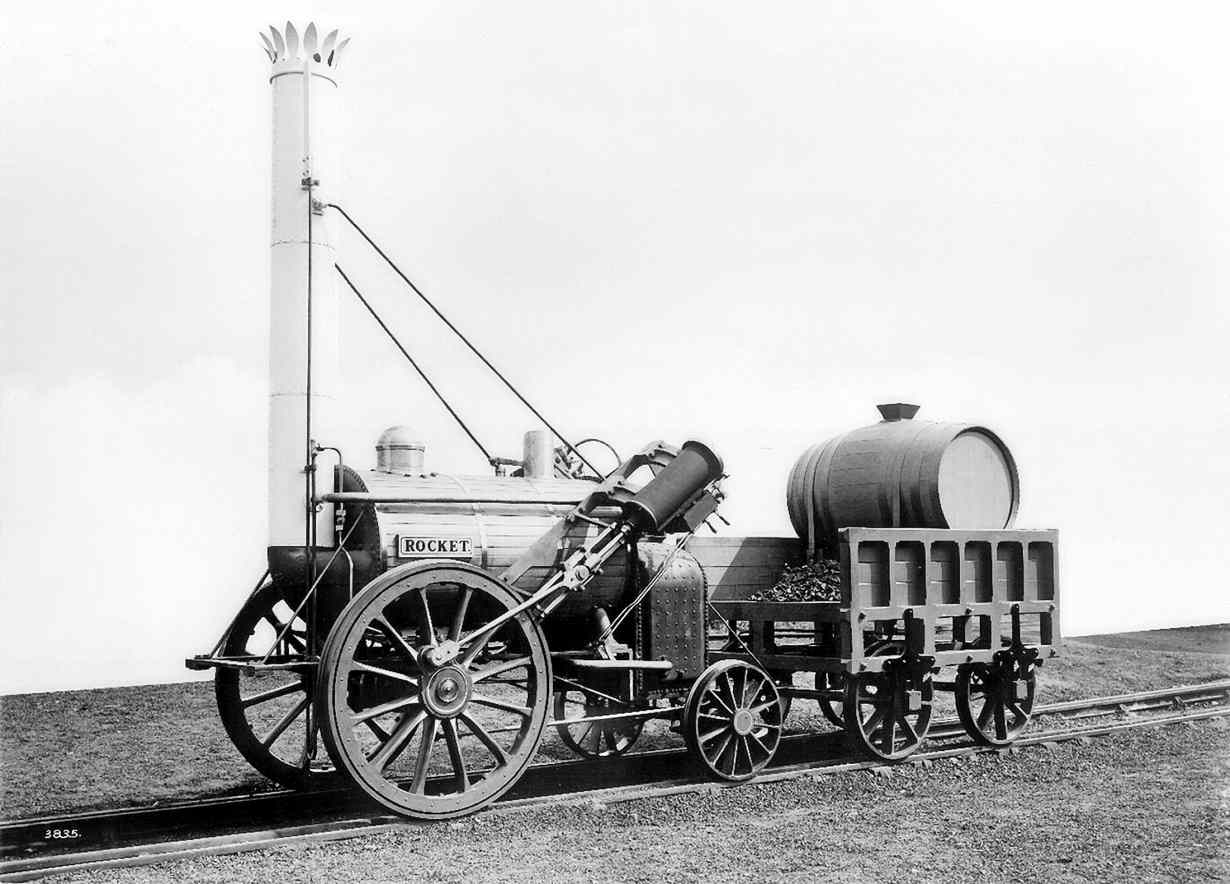

Stephenson’s Rocket needs scant introduction. It was to all intents and purposes a trophy machine, built primarily to win a competition, the Rainhill Trials of October 1829, which was held not only to find a locomotive capable of hauling regular trains on the world’s first inter-city line, the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, but to answer the question once and for all as to whether steam traction was the future of rail transport, as opposed to horse power or cable traction.

Enjoy more Steams Days Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

It had been a quarter of a century since Cornish mining engineer Richard Trevithick had given the first public demonstration of a steam railway locomotive, on the Penydarren Tramroad, near Merthyr Tydfil. However, while there were those who noted his invention, there were few prepared to take up the challenge commercially, and it was only during the time of the Napoleonic Wars, which provoked an acute shortage of supplies of horses and their feed, that northern colliery owners, anxious to ship their products to market, took a second look. As it was, Trevithick made no money from his world-shaping invention and indeed died in poverty.

While George Stephenson is popularly credited with building Rocket, it was his son Robert who took charge of its design and construction at the family firm of Robert Stephenson & Co in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, while in regular communication with George, and he may have been responsible for a lion’s share of the project.

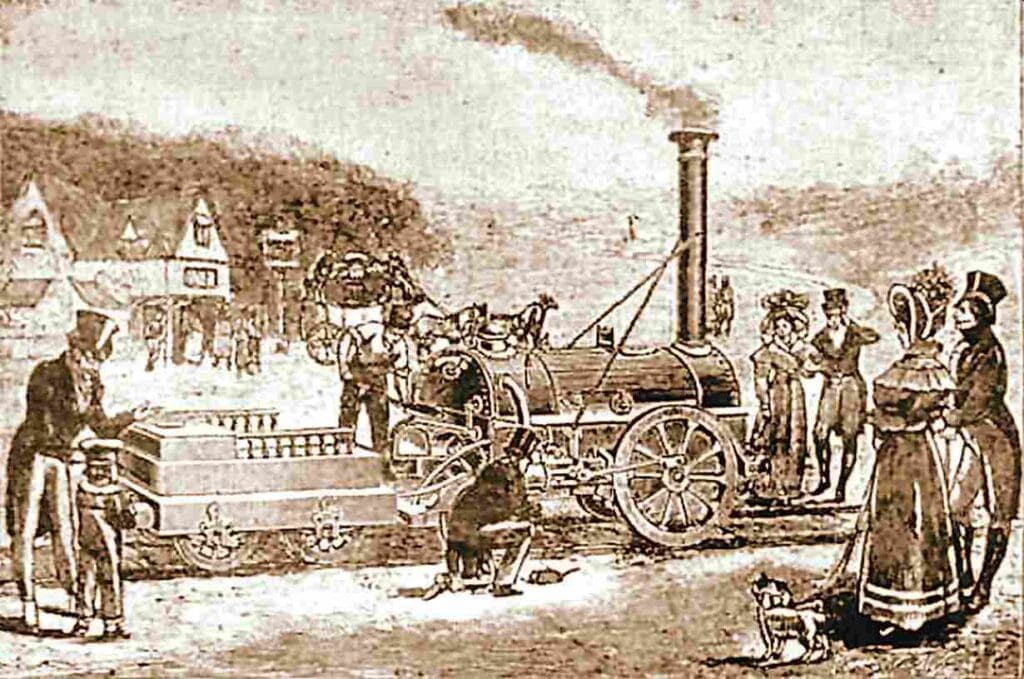

Huge crowds attended the trials, which began on October 6 – a grandstand was erected to accommodate them – and ultimately, Rocket was the outright winner from a total of five entrants.

Not only did the 0-2-2 win the £500 prize, it was immediately recognised as the most advanced steam locomotive of its day. On the last day of the trials, it hauled a carriage, conveying 25 passengers up an incline at 20mph.

By then no means the world’s first successful steam locomotive, its revolutionary features included a multi-tubular boiler with a firebox separate from the boiler and built to double thickness, with 25 copper pipes taking the heated water into the boiler. These innovations provided the blueprint for future steam locomotive development worldwide.

Accordingly, Rocket received star billing at the opening of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway on September 15, 1830, where the chief guest was the Tory Prime Minister, Arthur Wellesley, the first Duke of Wellington. Three special carriages had been built for the occasion, the finest of all for the Duke, whose train was hauled by Rocket-style 0-2-2 Northumbrian.

The official opening trains stopped at Parkside station, 17 miles from Liverpool, the halfway point of the line, so the locomotives could take on water, with passengers being told to stay on board. Sadly, Liverpool MP William Huskisson, who had earlier fallen out with the Duke and resigned from his cabinet, wanted to renew their friendship and alighted from his train to walk over to the Duke’s plush carriage. The two men shook hands, and Huskisson was so elated he did not see Rocket approaching on the parallel track. Driver Joseph Locke could not slam on Rocket’s brakes – because it did not have any.

Realising the danger too late, Huskisson pressed himself against the side of the carriage, and grabbed a door handle, but the door swung open. Rocket collided with the door, Huskisson fell on to the tracks in front of the oncoming train and sustained fatal leg injuries, dying later that night. It was not the world’s first railway fatality as is so often erroneously reported, but the first to be given widespread publicity. Needless to say, it left a black cloud over what should have been a triumphant day on what was a seminal moment in world history.

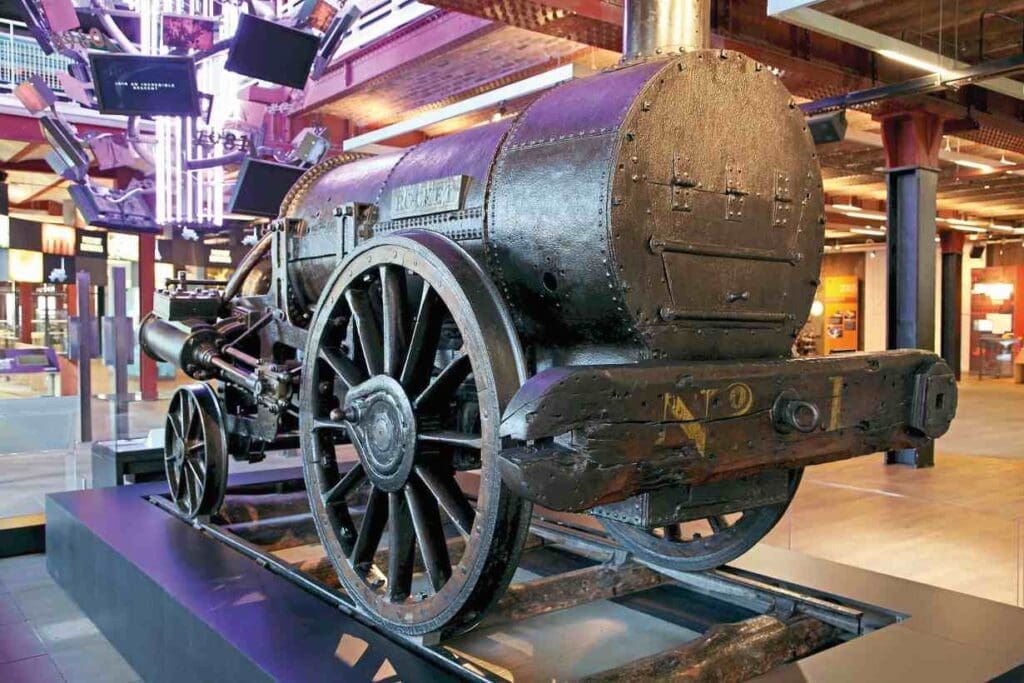

History soon overtook Rocket, the innovations of which quickly led to the development of more advanced locomotives. In 1834, it was modified as a testbed for unsuccessful experiments, its cylinders and driving rods removed, with two of the engines installed directly on its driving axle with a feedwater pump in between. The experiment proved to be a failure, but Rocket had already set out on a course that would completely change its appearance from that of the popular image in which it has been immortalised.

In 1836, Rocket was taken out of storage and restored, and sold to the Earl of Carlisle’s Brampton Railway, a mineral railway on the borders of Cumberland and Northumberland that served eight collieries and had recently converted to standard gauge. It was sold again in 1838 to J Thompson, a nearby colliery owner.

Rocket was withdrawn by 1840, and returned to the Forth Street works in Newcastle, where it was built. It was hoped to have it displayed at the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in 1851, but that never happened.

In 1862, it was given to the Patent Office Museum in London by the Thompson family. The Patent Office Museum became the Science Museum in 1909.

By then, Rocket was very different in appearance to the Rainhill Trials winner, having been repaired, modified or adapted over the years, but the legend would never die.

Flattery leads to multiple imitations

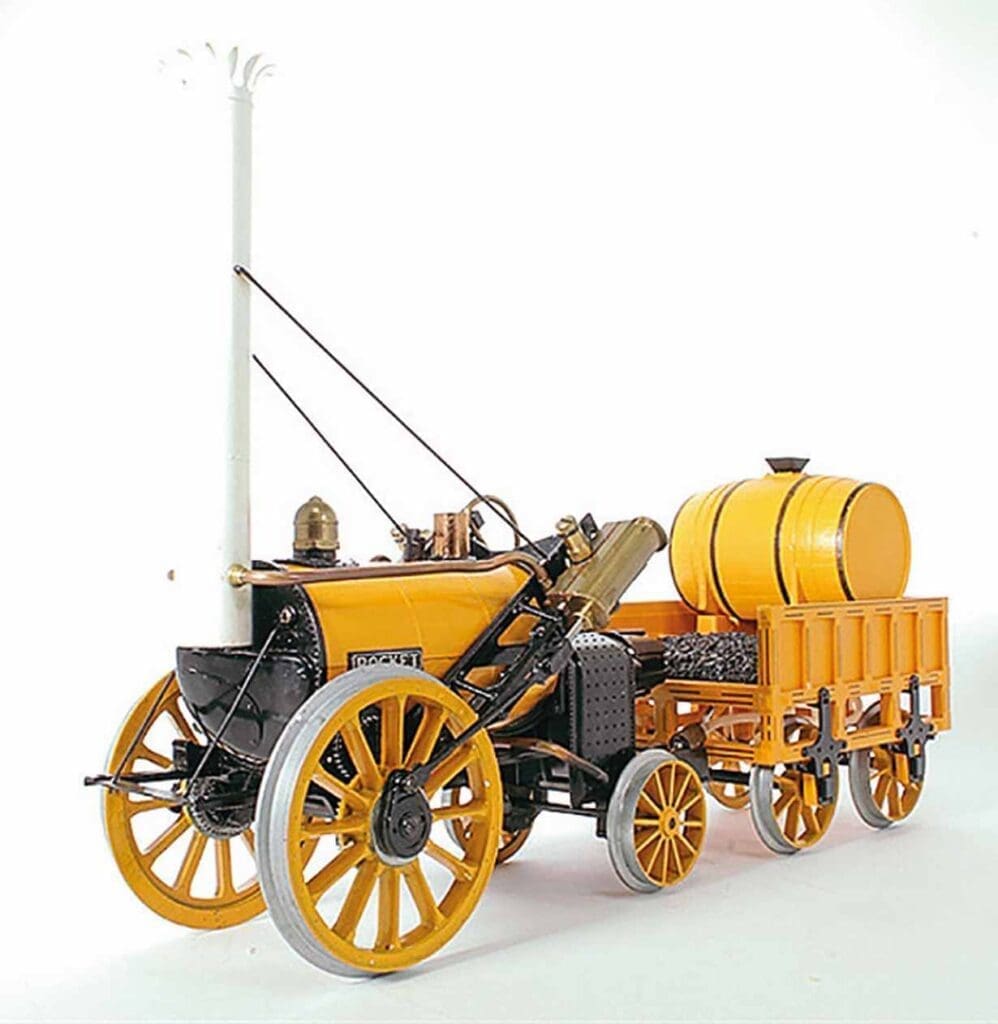

Rocket in its bright yellow livery became the defining symbol of a watershed moment in history in which railways developed the power to shrink the world, eclipsing all steam locomotives that had preceded it.

While the surviving locomotive, now relegated to being a permanent static museum exhibit, bore scant resemblance to its once-proud former self which ran on the Liverpool & Manchester, there were those who saw mileage in parading it to an enthusiastic and admiring public again – if only as a replica. Indeed, Rocket has attracted more attention from replica makers than any other locomotive, and over a far longer time span.

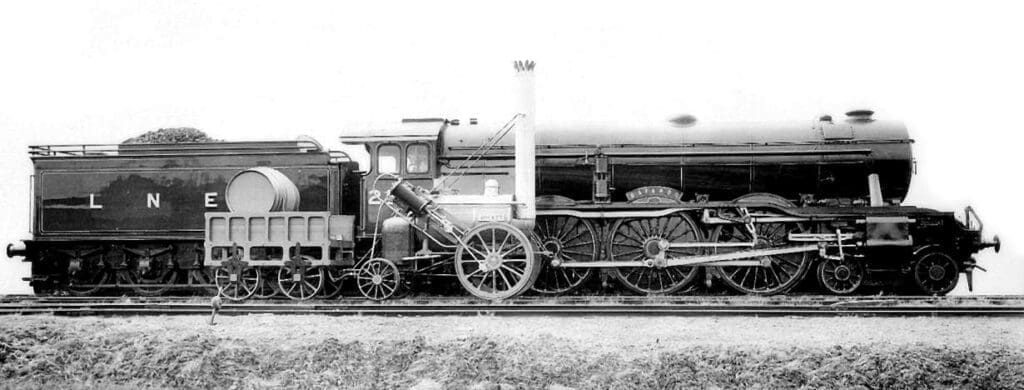

The London & North Western Railway’s chief mechanical engineer Francis William Webb built what would be the first of several full-size replicas at Crewe in 1881, for the centenary of George Stephenson’s birth that year. The LNWR was a successor to the Liverpool & Manchester, having been formed by the Grand Junction Railway, the London & Birmingham Railway and the Manchester & Birmingham Railway in 1846, and so it could legitimately use Rocket’s historical fame to reinforce its position at the Premier Line.

It was recorded that the replica Rocket was displayed at the International Exhibition of Navigation, Commerce and Industry in Liverpool, which was opened by Queen Victoria on May 11, 1886. Liverpool was hailed as the British Empire’s principal port at the time, and the colossal, lavish expense of the event included an African village, 50 natives of India and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and camel and elephant rides.

LNWR publicity material continued to feature images of the replica for several decades. It was rebuilt in 1911, and was again exhibited in Liverpool in 1930 during celebrations to mark the centenary of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway. The replica was displayed on a raised platform outside the Museum of British Transport in Clapham, London from 1963 for a decade, after which it was scrapped, the wooden parts having rotted away.

A second replica was built, at Mount Clare in Maryland, USA, for the Columbian World’s Exposition in 1893, and it was displayed again at the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad’s Fair of the Iron Horse in 1927. Nothing more was heard of it afterwards.

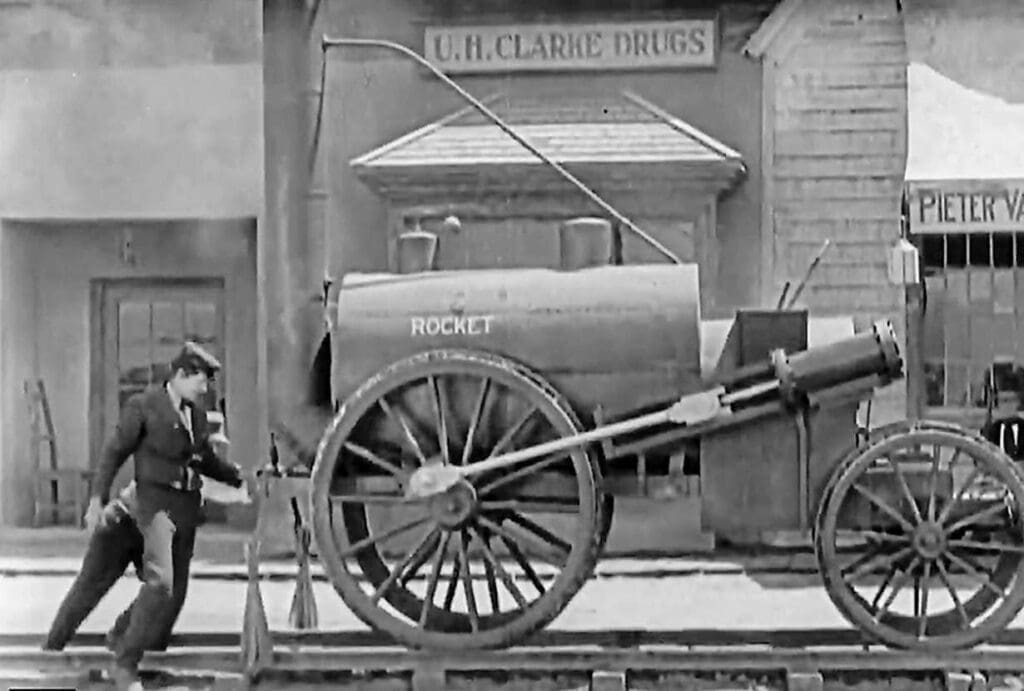

What was either a working replica or a convincing movie prop was built in 1923 for the Buster Keaton silent movie Our Hospitality – a film based in the Wild West. It was very much a ‘broad brush stroke’ copy, and has the name Rocket painted on its side.

This replica appeared in the Al St John film The Iron Mule two years later, directed by Keaton’s mentor, Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle.

The fate of this replica is also lost in the mists of time: it may well have been discarded as a spent prop after the second movie was made.

Robert Stephenson & Hawthorns supplied and exported a replica Rocket to motor car magnate Henry Ford in 1929.

Unlike the version that appeared in the earlier Hollywood movies, Ford demanded it should be built to exacting standards.

He used it on his private track within his Greenfield Village museum in Dearborn, Michigan. That museum is now the Henry Ford Museum, and the replica took pride of place in the hall of fame, highlighting the great landmarks of the Industrial Revolution. It last steamed in 1949.

Three more replicas to the same plan and detail were built by none other than Robert Stephenson & Co in the Thirties. Indeed, it has been speculated one of these, and not the LNWR replica, was the one displayed at Liverpool in 1930.

One of the three was built for the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry, and the other two, sectioned to show the inner workings, were constructed for the Museum of the Peaceful Arts in New York – what became the New York Museum of Science and Industry – later being moved into the Rockefeller Center, and Britain’s own Science Museum.

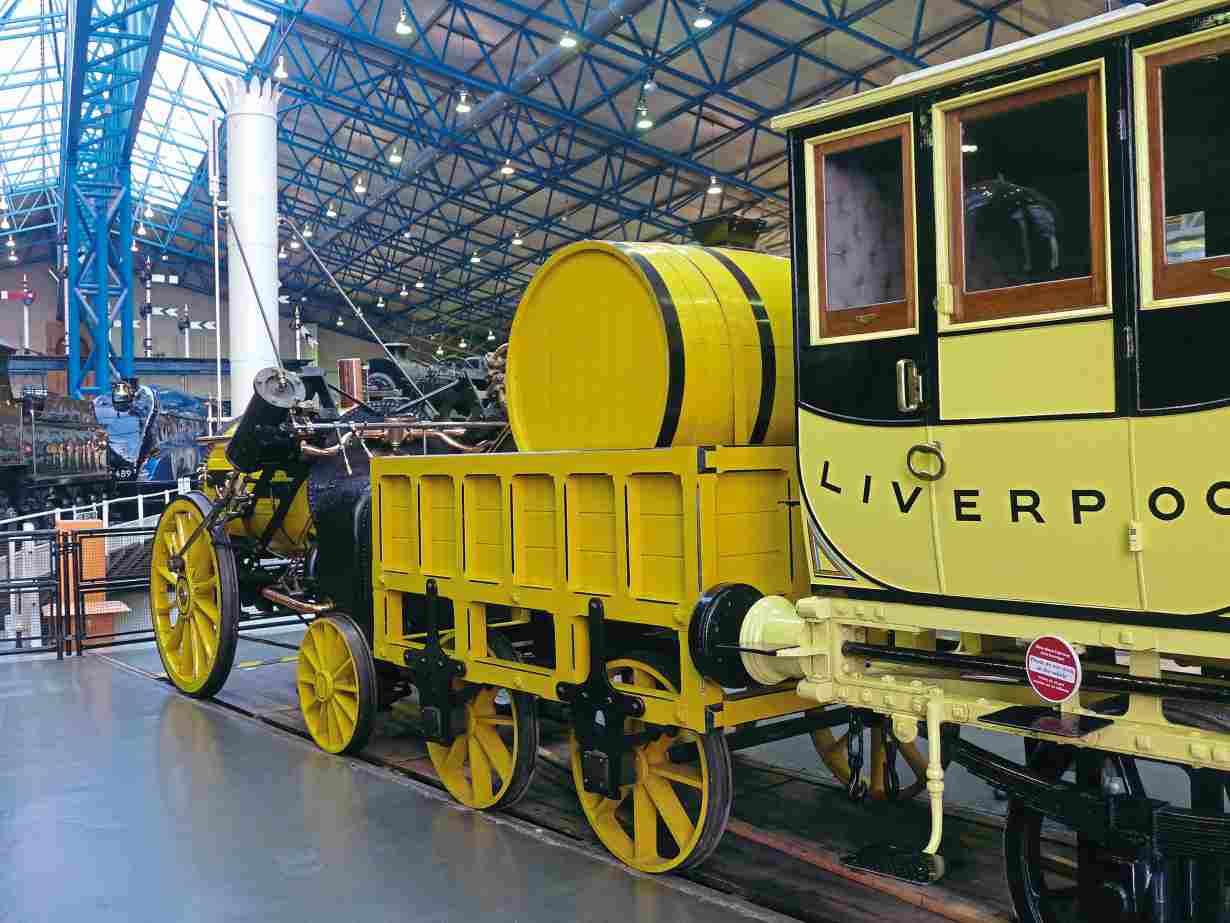

The latter static replica, constructed in 1935 and displayed alongside the original in the Science Museum, now stands in the Great Hall at the National Railway Museum, along with a pair of replica Liverpool & Manchester carriages, and is one of the venue’s most popular exhibits.

By contrast, the current whereabouts of the New York replica remain unclear. It seems to have found new owners: a locomotive listed in a classic car auction catalogue as a sectioned replica of Rocket reportedly sold for $42,000 in 2004, and there is speculation it may now be in private hands in southern California, possibly Los Angeles.

Rumours have occasionally surfaced that it is being restored to steamable condition!

Today’s working Rocket – built twice over!

A magnificent working replica of Rocket was built in 1979 by engineer Mike Satow and his Locomotion Enterprises for the Rocket 150 anniversary celebrations at Rainhill. This replica used some of the parts from the scrapped LNWR replica of 1881. Mike salvaged the metal components from the Clapham exhibit, including the frames (with modifications), trailing and tender wheelsets, upper chimney and sundry other bits and pieces. First of all, however, it was displayed in Kensington Gardens, London.

A frequent and popular visitor to heritage railways, it was fitted with a chimney shorter than the original in order to the clear the bridge at Rainhill, as there is now less headroom than when the line was built in the 1820s. It is now based at the National Railway Museum, and frequently visits heritage lines around the country.

In 2002, it featured in a ‘replay’ of the Rainhill Trials staged at the Llangollen Railway for the BBC TV programme Timewatch – Rocket and its Rivals – using modern-day replicas of the original contestants. Even though the locomotives were not the same, the winner was Rocket!

The 1979 Rocket also has the unique claim to having been built new twice.

In 2009 it was dismantled for overhaul and completely rebuilt by Victorian locomotive restoration experts at chartered surveyor and heritage steam engineer Bill Parker’s Flour Mill Colliery workshops at Bream in the Forest of Dean, not only with a new boiler, but also new frames, the single component which gives a locomotive its identity. It returned to steam the following February.

The modern-day working replica of Rocket being rebuilt for the second time. Originally constructed in 1979, in 2010 it was taken to the Flour Mill workshop at Bream in the Forest of Dean, a market leader in the restoration of Victorian locomotives, to be overhauled. The plan was to replace the boiler. However, it was discovered the replica’s frames were significantly out of size from the original design, so in the interests of accuracy it decided to start again with new frames, and then design the new boiler to fit the correct frames. As a result, the only components that still fitted were the front wheels and the cylinders, but all the fixings had to be new, because the diameter of the boiler to which they are all attached is different. Even the back wheels had to be replaced because they were the wrong diameter. Convention holds that the frames are the single component which gives an identity to a locomotive, and as they were replaced, the end product, which subsequently underwent running-in trials on the Avon Valley Railway, is in theory a new locomotive! BILL PARKER

Back to the North

Over the decades, Rocket has formed the basis of countless models, toys and ornaments.

In the Thomas & Friends television series, it was portrayed as Stephen, a friend of Sir Robert Norramby, Earl of Sodor. The name Stephen comes from its designer, Stephenson.

So the Rocket legend persists and with the passage of time continues to grow even bigger in stature, a permanent reminder of the time when Britain led the world in technology.

Having been displayed in the Science Museum since 1862, Rocket was loaned to Tyneside’s Discovery Museum between June 22 and September 9, 2018, as a key exhibit in the landmark Great Exhibition of the North.

During the 80 days Rocket was on display, it was seen by more than 176,000 visitors. Discovery Museum and archives manager Carolyn Ball said: “It’s been hugely popular and one of the star attractions.”

On September 20, it was removed and taken by lorry to the Museum of Science & Industry in Manchester – which incorporates Liverpool Road station, the eastern terminus of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway into which Rocket would have regularly ran shortly after the line opened. It remained on display until late-April 2019 – afterwards becoming a permanent exhibit in the National Railway Museum in York, where both its working and cutaway replicas are already based.

Looking inside a legend!

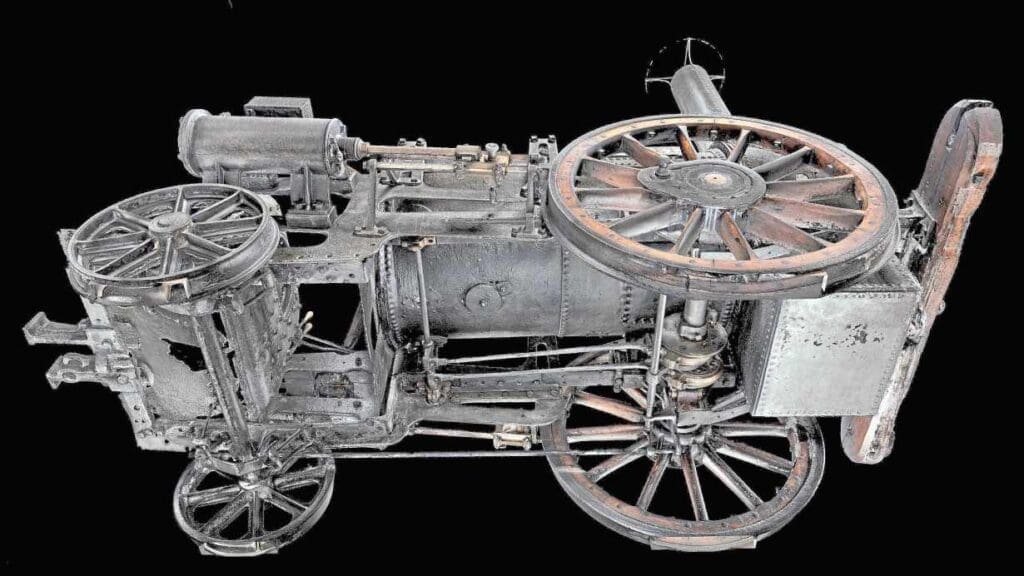

In 2018, the Science Museum Group published a high-resolution 3D model of Rocket, enabling audiences across the globe to examine it in unprecedented detail. Working with Science Museum Group colleagues, a team from ScanLAB spent 11 hours recording every angle of the original to create the 3D model using more than 200kg of camera, lighting and scanning equipment.

Scanning and photography was particularly challenging due to Rocket’s colour, glossy texture and complex shape.

It was created using 22 high-resolution LIDAR scans and more than 2500 detailed photographs. After six weeks of processing the LIDAR data and 220 gigabytes of photography, a highly detailed point cloud was produced, containing spatial coordinates, colour and intensity values for a staggering 750 million points.

A further two weeks of processing was needed to produce several 3D models of Rocket, one of which – featuring 84,000 vertices – was published as Rocket went on display at the Science & Industry Museum in Manchester (see above). Rocket’s legendary efficiency and performance innovations, all of which are highlighted on the 3D model, include the multi-tubular boiler design and blastpipe, the use of a single pair of driving wheels, with a small carrying axle behind, and cylinders closer to the horizontal, all of which helped make the locomotive the fastest locomotive of its time.

Its ground-breaking design became the basis for subsequent steam locomotive development over the next 150 years.

The 3D model of Rocket has been published on the Science Museum Group Collection website at https://tinyurl.com/y5863pbn. Audiences can move the 3.3-ton locomotive around with ease on screen, inspect underneath and explore the innovations.

The model can also be downloaded from Sketchfab (sketchfab.com/models) under a Creative Commons non-commercial licence, enabling users to 3D print their own model of Rocket.

Measuring more than 13ft in length, Rocket is the most complex and largest item from the Science Museum Group Collection to be scanned.