It is not often the name of a railway locomotive becomes adopted as an everyday saying in the English language, but many believe that happened in the case of the world’s oldest surviving steam locomotive.

This is just one of the many in-depth features found in the new book by Robin Jones, Legendary Locomotives, available now from Classic Magazines.

IT IS generally accepted the world’s first steam railway locomotive was built by Cornish mining engineer Richard Trevithick at Coalbrookdale in 1802, but it was, as far as can be ascertained, never demonstrated in public, and it is believed few people ever saw it.

Enjoy more Steams Days Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

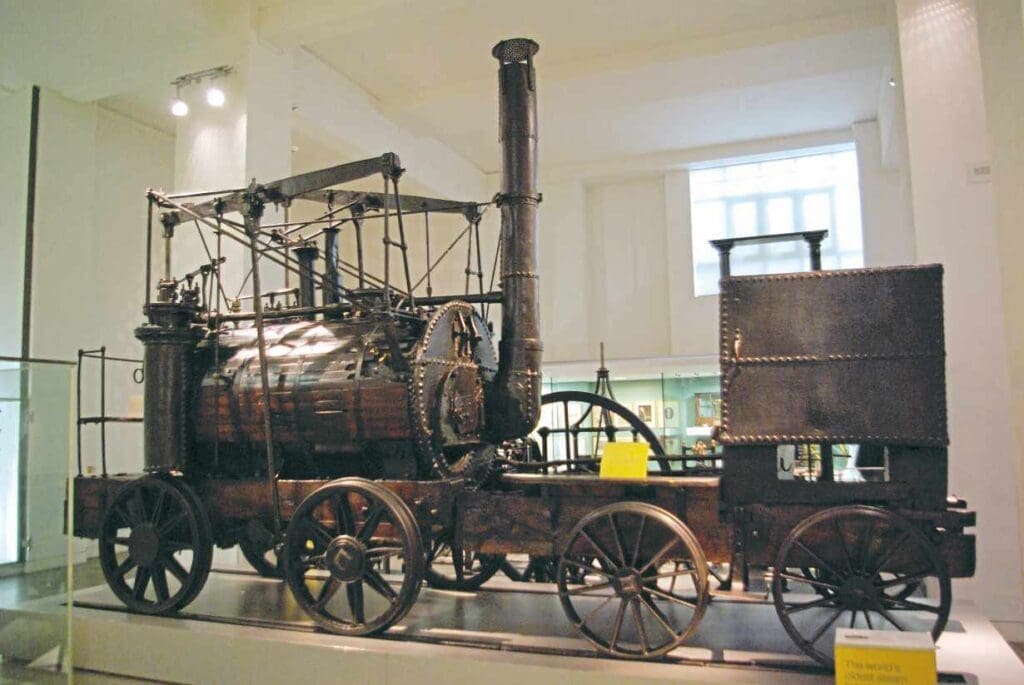

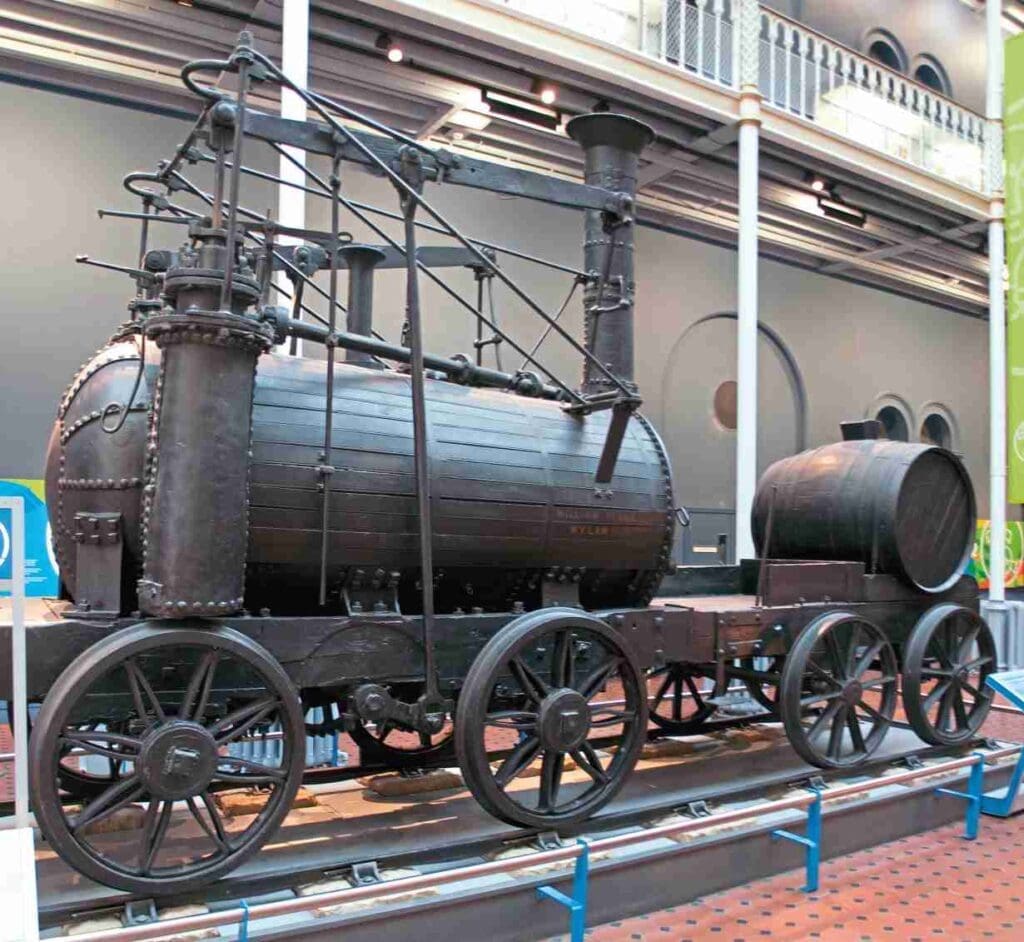

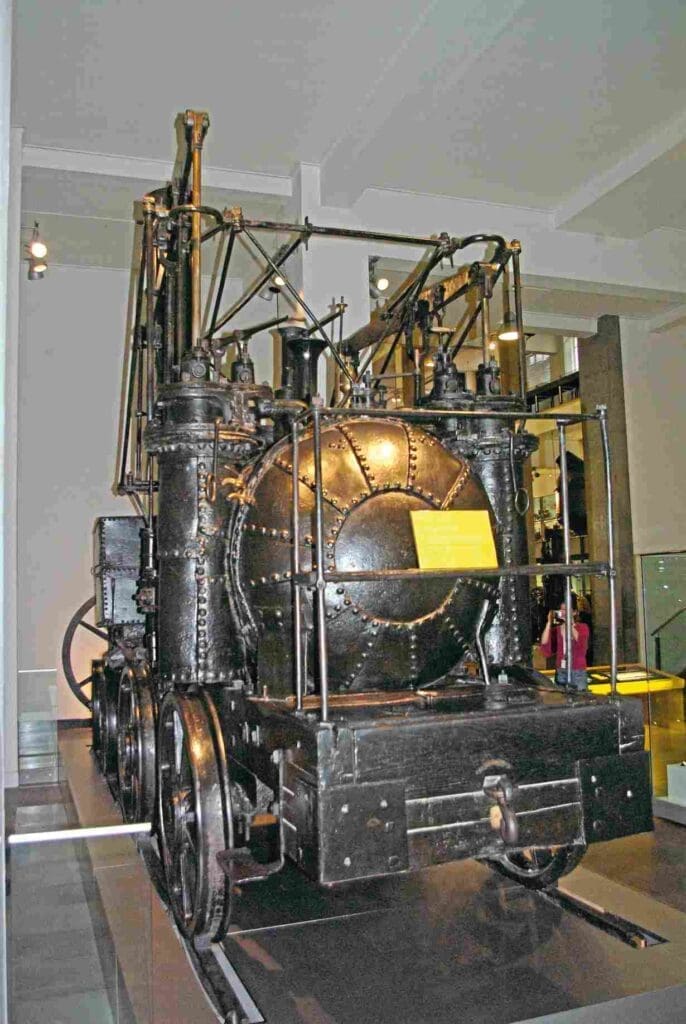

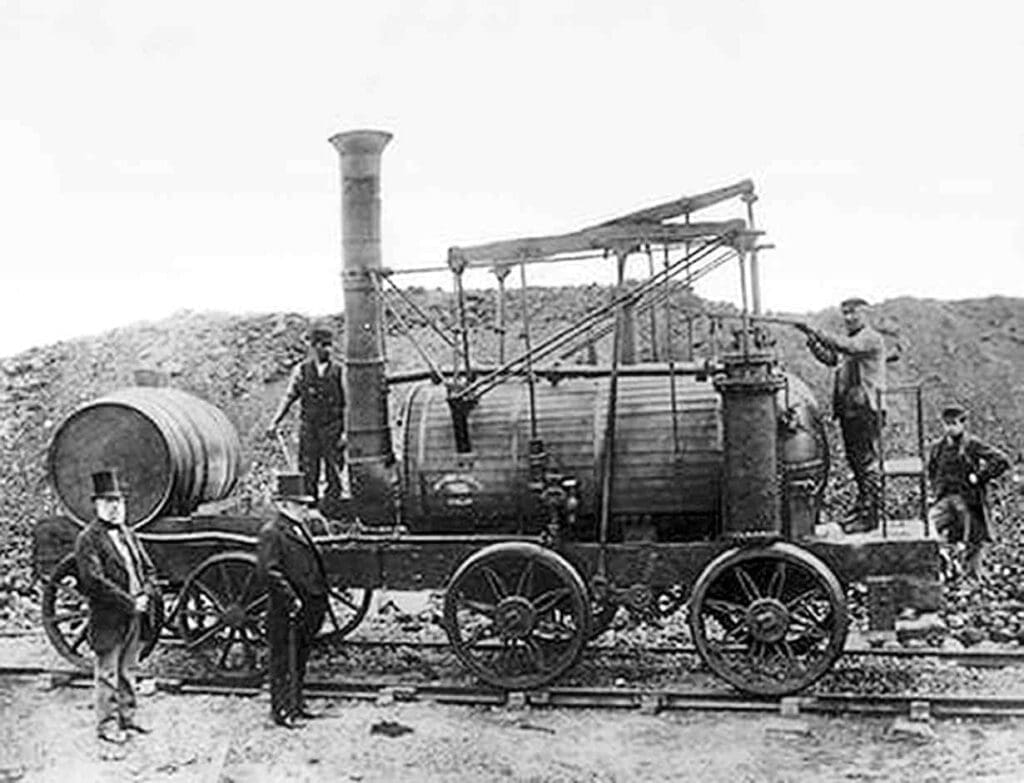

The oldest surviving steam railway locomotive in the world is Puffing Billy, which was built in 1813/14 for Christopher Blackett, owner of Wylam Colliery, near Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

In 1805 Blackett had held talks with Trevithick, who supplied him with drawings of a steam locomotive. The locomotive, of which only very basic details survive, was built by foundry owner John Winfield and was running at Gateshead in May 1805. It was designed to be lighter than the locomotive demonstrated by Trevithick on the Penydarren Tramroad in 1804, and which broke the rails because of its weight.

Blackett’s 5ft-gauge waggonway was made of wooden rails. Trials of the locomotive were carried out, but Blackett did not want the locomotive and its perceived difficulties. Instead, it was said to have been converted into a blower for the foundry.

Blackett approached Trevithick again in 1808 having relaid his five-mile waggonway as an iron plateway, arguing that this time it might well stand the weight of one of his locomotives, but he said he was too busy to oblige.

So Blackett instead asked his colliery superintendent William Hedley to build him a locomotive.

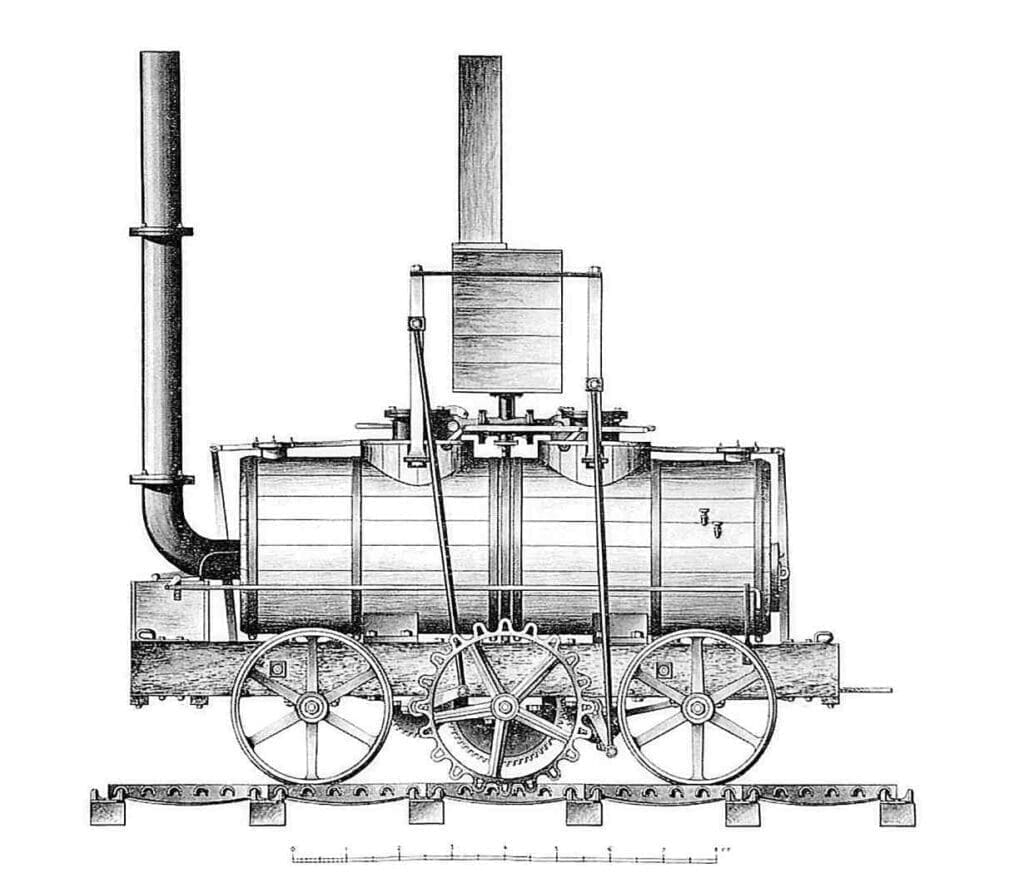

At first, the pair looked at converting the Wylam waggonway to a rack-and-pinion system, as designed by Middleton Colliery coal viewer and inventor John Blenkinsop.

Blenkinsop had looked at Trevithick’s locomotives and drew the conclusion their big problem was lack of adhesion. Trevithick’s relied on their weight to stop them slipping, but in the process broke the rails. So make locomotives lighter? The problem then would be they could not haul as many wagons.

Blenkinsop invented a scheme whereby the locomotive would gain extra adhesion through a central cogwheel which would engage with a toothed third rail in the centre of the track. He therefore invented the world’s first rack-and-pinion railway and took out a patent for the design, decades before any were built to ascend the Swiss Alps. Thousands of locals were amazed by the first locomotive as it ran light engine at 10mph during its trial run on the 4ft-gauge Middleton Railway, and then several of them jumped aboard the wagons for a ride. It was estimated Blenkinsop’s locomotives could do the task of 50 horses.

His locomotive Salamanca was the world’s first commercially successful steam locomotive on the first commercially successful steam railway, which led to the colliery’s profits soaring within two years thanks to its ‘modern’ transport taking coals to market.

Blackett considered that converting his Wylam waggonway to a Blenkinsop rack-and-pinion system would be far too expensive, despite the rave reviews it was generating.

Trevithick was right all along

So Hedley went back to the Trevithick formula, to see if sufficient adhesion could be obtained using a smooth wheel on a smooth rail after all.

In 1813, he experimented with a carriage operated by four men, two each side standing on stages suspended from the frame. Each man turned a handle connected by a cross shaft to the one on the handle on the other side. A gear was set on the cross shaft, and in turn it engaged with a gear set on the wheel axle, thereby turning the wheels and moving the carriage along the plateway.

The carriage was loaded with various weights before more and more loaded coal wagons were attached until the wheels slipped. Hedley’s experiment was a success: it proved that a sizeable train of loaded wagons could be hauled by the friction available from the driving wheels of a locomotive.

Hedley then upgraded the carriage into an experimental locomotive by adding a cast iron boiler, with one cylinder connected to a flywheel.

This ‘travelling engine’ as it was dubbed may have been nicknamed Grasshopper. Prone to stalling, and very much underpowered, it was not a success, but no matter – Hedley learned sufficient lessons in the process to design another locomotive, built by Wylam colliery’s enginewright Jonathan Foster, with the aid of foreman blacksmith Timothy Hackworth.

The end result was markedly different to both Trevithick’s and Blenkinsop’s locomotives, and indeed, many others that would follow afterwards.

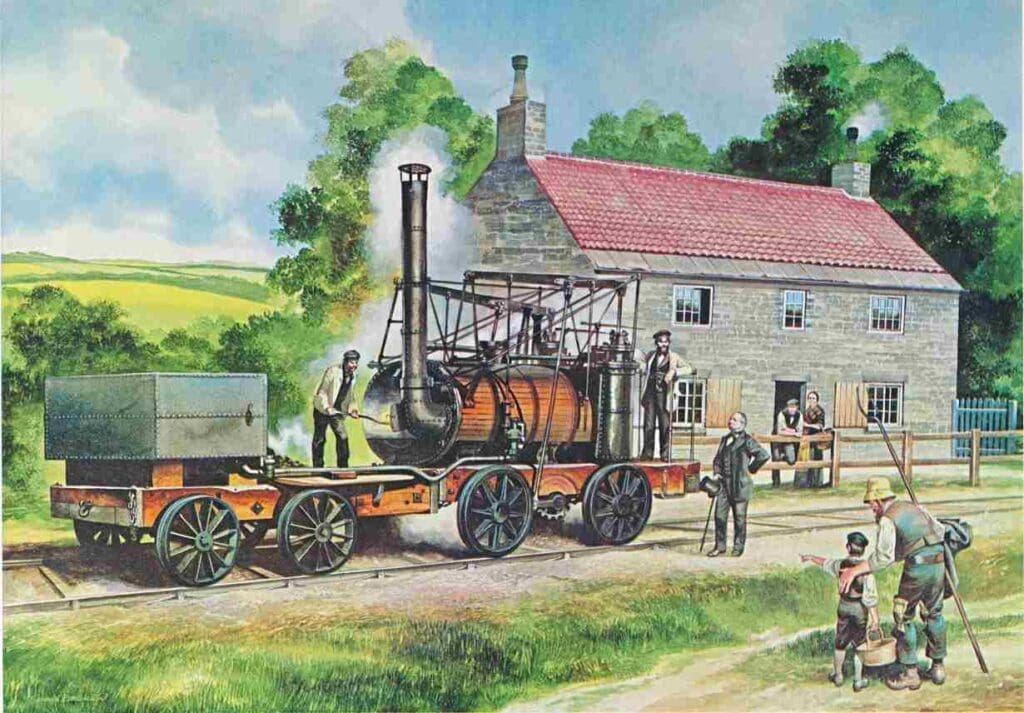

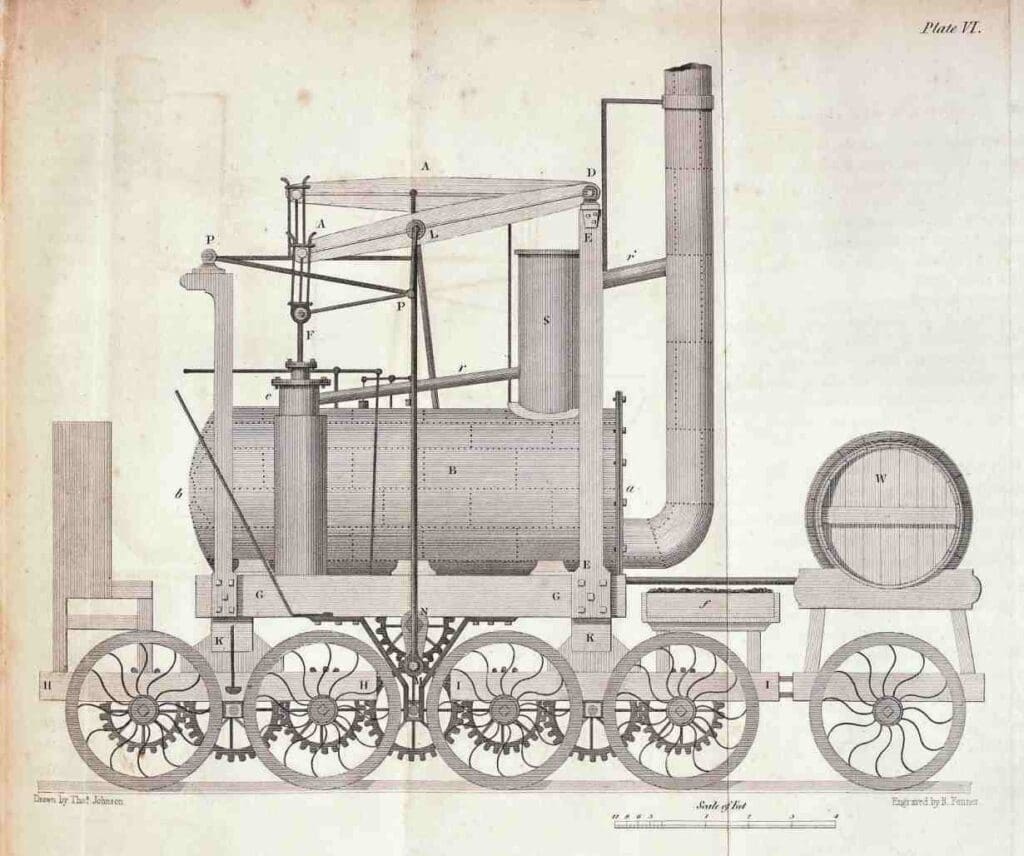

Puffing Billy incorporated a number of novel features, patented by Hedley, which were to prove important to the development of locomotives. It had two vertical cylinders on either side of the boiler, and was partly enclosed by it. It drove a single crankshaft beneath the frames, from which gears drove and also coupled the wheels allowing better traction. A tender was attached to the chimney and firebox end to carry water and coal. Designed as a four-wheeler with flangeless wheels, it was converted to an eight-wheeler to share the load after the plate rails snapped. When the waggonway was relaid, it was converted back to four.

Hedley’s locomotive became known as Puffing Billy, a name that also entered the English language in phrases such as “puffing like Billy-o”.

Another explanation is that the name derived from Joseph Billio, a hard-core Puritan ‘hellfire and damnation’ preacher at the United Reformed Church in Market Hill, Maldon, Essex, around 1696. Maldon townsfolk are convinced this that is the true origin, although the phrase did not enter common usage until long after Billio’s death.

A success in its day, Puffing Billy regularly hauled trains of 50 tons between 4-5mph for nearly half a century, during which time it was repeatedly modified. It retired in 1862 and was eventually loaned by then colliery owner Edward Blackett to the Science Museum, which subsequently bought it off him for £200, where it is now on permanent display.

Wylam Dilly and Lady Mary were two similar locomotives built to improved Puffing Billy designs.

Puffing Billy and Wylam Dilly were both rebuilt in 1815 with 10 wheels, but were returned to their original condition in 1830 when the railway was again relaid with stronger rails.

‘Dilly’ was the name given to steam locomotives at Wylam Colliery. Wylam Dilly is preserved at the Royal Museum in Edinburgh.

The Wylam Waggonway ran past the front door of a cottage in Wylam village. It was there, in 1781, that George Stephenson was born. As an infant, he would have daily views of the trains passing close by, and one day he would invent a locomotive that would change the world. Adhesion-worked railways were clearly the way forward.

By the mid-1830s, Blenkinsop’s rack systems had ceased operation, as they had by then long since been superseded by them.

It was not only George Stephenson who was influenced by Puffing Billy. In 1952 British light music composer Edward White wrote a melody named after the locomotive. It became the theme tune to the BBC Light Programme’s Children’s Favourites from 1952-66.

Puffing Billy – second time around.

Beamish Museum, in County Durham, has long been recognised as both the world leader in the study of early steam railways and the building of period replicas. That is both apt and ironic, because Durham is considered by historians to be the cradle of the steam railway, if not its birthplace.

In 1975, Beamish staff built a working replica of Locomotion No. 1, the first locomotive to run on the Stockton & Darlington Railway, the world’s first public steam railway, on September 27, 1825.

While several locomotives from the embryonic age of steam survive, to return them to running order would be all but unthinkable. The sheer amount of original material which would need to be discarded and replaced – don’t even mention the need for upgrading the design to modern safety methods – would severely damage their value as artefacts. So if you want to see them run again, build a replica!

In 2002, one of the most remarkable and distinctive of all new-build early locomotives was unveiled by Beamish Museum. The colossal Steam Elephant was an early locomotive that the world had all but completely forgotten.

All that had survived as evidence of the existence of this oversized and unwieldy beast of 1815 – very much a local and unique design by John Buddle and William Chapman for Tyneside’s Wallsend Colliery – was a contemporary painting and a handful of basic sketches.

Yet from a mere handful of such evidence, combined with exhaustive technical research, Beamish Museum staff produced a new set of engineering drawings and set to work on replicating this mammoth of the dawn of steam.

The Steam Elephant now also runs on the museum’s Pockerley Waggonway.

Next on the Beamish ‘to do’ replica list was none other than Puffing Billy.

Construction of a £400,000 Puffing Billy replica began in 2002, partially financed by the Hedley Foundation, a charity originally established by the descendants of William Hedley.

The 21st-century version was built to drawings produced by Dave Potter, with the boiler designed by Graham Morris, owner of Leighton Buzzard Railway-based Kerr, Stuart 0-4-0ST Peter Pan, with the project jointly overseen by Beamish’s Jim Rees.

The locomotive, assembled by builder Alan Keef of Ross-on-Wye, Herefordshire, arrived at the museum in April 2006 and was immediately put through it paces.

he ‘second’ Puffing Billy also double-headed with the Steam Elephant replica over the Pockerley Waggonway. Shakedown trials, crew training and final testing by HM Railway Inspectorate followed, with Puffing Billy the second officially launched in July that year.

More fame was yet to come for this replica of an early steam legend.

In April 2017’s Great North Festival of Transport, the Puffing Billy replica ran on the colliery line at Beamish Museum, coupled to a rake of chaldron wagons for the first time. PAUL JARMAN/BEAMISH MUSEUM

The Steam Elephant replica (left) and that of Puffing Billy on the Pockerley Waggonway at Beamish Museum. The waggonway opened in 2001, and represents the year 1825, the year the Stockton & Darlington Railway opened, the world’s first public steam-operated passenger line. The engine shed is of a decidedly contemporary design. BEAMISH MUSEUM

Beamish Museum’s £400,000 replica of Puffing Bully, newly arrived on April 27, 2006. BEAMISH

In Whitsun 2007, the Puffing Billy replica was the star guest at the Dutch Museum Buurtspoorweg’s 40th anniversary celebration.

The visit to The Netherlands was a welcome opportunity for the Beamish staff to assess the abilities of the Hedley-designed locomotive over longer distances, in this case over the five-mile line from Haaksbergen to Boekelo.

From a historical point of view, the visit of the 1813-designed locomotive could be seen as a curiosity, as the first train in The Netherlands ran only in 1839, between Amsterdam and Haarlem.

Nevertheless it was a superb opportunity for the Dutch public to see in action one of the engines that marked the very beginning of locomotive engineering.